TNRC Introductory Overview - Beneficial Ownership Transparency and Natural Resource Corruption

Targeting Natural Resource Corruption

Harnessing knowledge, generating evidence, and supporting innovative policy and practice for more effective anti-corruption programming

Key Takeaways

- Beneficial ownership transparency (BOT) aims to uncover the identity of “beneficial owners” who ultimately control assets. BOT allows law enforcement and the public to track bad actors’ connections to other businesses and hold them accountable for any corruption, illegal activities, or illicit fund transfers.

- For the natural resource management (NRM) sector, progress in BOT could play a significant role in deterring corruption, particularly corruption that can infiltrate resource supply chains.

- Regulations around BOT are changing quickly, with dozens of countries enacting important rules to combat corruption and illicit money and trade in just the last few years. Even though many loopholes remain, it is important for NRM practitioners to understand the beneficial ownership rules at the sites where they are working and make use of BOT where possible to safeguard programs from natural resource crime and associated corruption.

This paper provides a brief introduction

to the concept of beneficial ownership, related transparency issues, and their impact on conservation and NRM objectives. It complements other TNRC resources on sector-specific impacts of opacity in beneficial ownership information, financial crime, and trade-based money laundering, to help orient practitioners to corruption risks and responses in those spaces.

Why should conservation and NRM practitioners care about BOT?

Illicit supply chains, including illegal wildlife trade (IWT) as well as illegal forest and fisheries products, rely on corruption at all levels. In both the trade and the corruption, there is movement of money or value. Criminals, corrupt officials, and private actors work hard to avoid detection, prosecution, punishment, and taxation of the profits from their criminal and corrupt actions. So, while a common expression for combatting illicit trade and corruption is to “follow the money,” when the owner of the money, company, fishing vessel, or logging concession is unknown, it can be nearly impossible to use this approach. Banks and other financial institutions can’t do effective due diligence on their clients, and authorities can’t trace illegal actions back to the people who enjoy the profits. As a result, the powerful financial incentives to engage in illegal and unsustainable exploitation of natural resources and species continues.

What exactly is beneficial ownership?

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) defines a beneficial owner as the “natural person(s) who ultimately own(s) or control(s) a customer and/or the natural person on whose behalf a transaction is being conducted.” The concept also includes “those persons who exercise ultimate effective control over a legal person or arrangement.” More simply, a beneficial owner of a company[1] or entity is the human person who ultimately controls the decisions of the company and/or benefits from its success.

Beneficial ownership transparency is the availability of information about who that ultimate owner is. There is no singular method for achieving this transparency and harmonizing it across jurisdictions, but the common thread is to require that companies provide more complete and accurate information about their beneficial owner(s) and that this information should be accessible and verifiable to the public or, at the very least, to government and law enforcement.

Box 1: Additional terms of acquaintance for BOT

Shell company: an incorporated company that does not have significant operations, assets, business activities, or employees.

Front company: a functioning company that has all the characteristics of a legitimate business but serves only to disguise and obscure illicit (financial) activity.

Anonymous company or phantom firm: a corporate entity with purposefully disguised ownership so it can operate without public or legal scrutiny.

Consignor, Settlor, Trustee, Nominee: all persons or entities that might assist in creation or registration of a company and be named as legal owner.

Trusts: a relationship whereby property is held by one person while another has use and benefit of it. Often exempted from BOT, against best practice advice of advocates.

Bearer shares: like ordinary shares in a company, but the name of the owner of a bearer share is not recorded anywhere.

Legal person: a human or non-human entity that can be treated as a person for legal purposes, like owning property, being sued, or entering contracts.

Offshore: refers to outside the country or jurisdiction. In financial contexts it typically refers to operating or housing money or companies in another jurisdiction to take advantage of better tax rates, or to hide wealth and evade tax and business regulations.

How is beneficial ownership obscured?

There are many methods to obscure the true ownership of a company. These include using a shell company, listing a proxy as owner, or splitting ownership among multiple people, companies, or jurisdictions. As a result, determining the beneficial owner(s) of any company can be complicated, even though these methods are often legal.

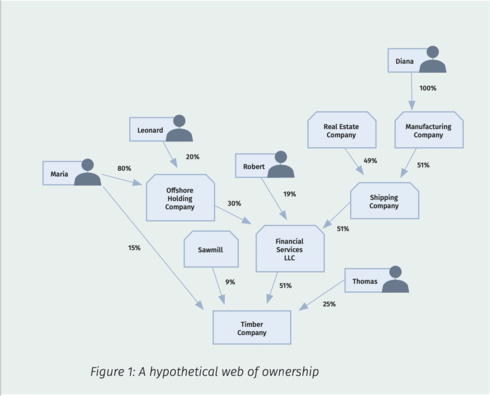

While jurisdictions vary, many define a beneficial owner as having 25 percent direct control and/or significant indirect control (i.e., the ability to terminate board members). In the example in Figure 1, that definition would mean that only Thomas and Maria are beneficial owners, while Robert, Leonard and Diana are not.[2]

Even this highly simplified diagram gives an idea of the complexities of many of these business arrangements and the opportunities for illicit practices that complexity presents. Although Diana owns only a single manufacturing company, the chain of ownership suggests that she could exert enough control over other entities (shipping company, financial services, and the timber company) to be able to conceal a variety of illicit practices throughout the supply chain. Meanwhile, the presence of the offshore holding company could enable all parties to launder illicitly-earned profits and transfer value out of the country.

Examples and impacts of obscured beneficial ownership

According to the OECD,

Corporate structures such as shell companies are attractive to criminals and corrupt officials for two main reasons: 1.) they provide an air of legitimacy; and 2.) they provide the ability to shield the identity of the beneficial owner because they are separate from the individuals behind the corporate veil…. For example, criminal funds can be disguised within legitimate business transactions by merging legal and illegal profits, which can be transferred either to other business entities or to domestic or foreign bank accounts….

In the NRM sector, FATF similarly notes, “both small-scale and large-scale criminals involved in [IWT] often use shell and front companies to conceal payments and launder the proceeds of their illicit activities.” Examples of exactly this have been found in many notorious NRM cases. For example:

- In one fisheries case, the same fishing vessel was owned by a Chinese company and also registered to a company in East Timor so that it was eligible for fishing licenses. Upon seizure in Indonesian waters, officials found that the ship had flown six different jurisdictions’ flags at various points as it tried to evade detection while fishing illegally. No individual was identified or held responsible as the beneficial owner, but some individual or individuals had surely profited from the scheme. As a result, nothing prevents this owner from committing the same scheme again.

- In one particularly egregious case investigated by Global Witness, political elites created shell companies to be able to sell themselves enormous tracts of land at a fraction of market value (and in violation of law and local peoples’ rights). The lands would then be sold at immense profit, but registered locally at a false, lower sum to avoid taxes. The real payments would then take place offshore in financial secrecy jurisdictions. A study by the US Government Accountability Office even found the family at the center of the scheme to be owners of property rented by the FBI in the US. Many other high-security property leases paid by the US government had no identifiable beneficial ownership information at all.

The need for public access

While most countries require registration of the legal owners of companies, bank accounts, real estate, and other assets, tracking the beneficial owner is a more recent phenomenon. The push for BOT was given a major boost by the 2016 Panama Papers revelations. Those disclosures revealed huge numbers of companies created with the assistance of “company formation services,” listing attorneys and other service providers as owners with no disclosure of who actually benefitted from company profits. A large number of “respectable” business people, politicians, and other public figures appeared in the more than 200,000 anonymous companies that shielded their assets from public view and possibly also from taxes or conflict of interest declarations. The Pandora Papers, released in October 2021, revealed the continued prevalence of the use of tax havens and shell companies to hide funds and obscure ownership information, highlighting the continued need for strengthened BOT.

The most effective BOT regimes publicly share the identity of beneficial owners of companies and other entities. According to Transparency International, such public registers “would allow dirty money to be more easily traced and make it more difficult and less attractive for people to benefit from the proceeds of corruption and crime.” Where data is either unavailable to the public or available for a fee only, it is more difficult for any organization to know who they are doing business with and therefore protect their work. Opacity of ownership information also makes it harder to investigate and prosecute those who benefit from illicit activity in the natural resource sectors.

Whether public or not, while requiring a beneficial ownership registry is a simple idea, implementing the policy and keeping the data updated is not. It can be technically complex, although resources exist like the Open Ownership Principles. Open Ownership’s resources spell out best practices for establishing (public) BOT registries, including detailed guidelines for ensuring accuracy of data through verification and making registries freely available to the public. Additionally, jurisdictions are subject to lobbying by local and international business interests to allow exceptions or restrict access, a process which must be managed carefully to avoid a race to the bottom.

The state of BOT around the globe

In recent years, support for beneficial ownership registries has grown. According to the Tax Justice Network, as of April 2020, 81 of 133 countries surveyed had some kind of BOT regulation, while just two years earlier, that figure was only 34 of 112. The UK was one of the first major economies to establish a publicly available corporate registry, in 2016, although notorious tax havens among its overseas territories were not initially included, and critics have pointed out that there is no designated staff assigned to monitor the accuracy of the registrations.[3] The US passed BOT requirements at the end of 2020, to be implemented in 2022. Even though the US BOT legislation leaves substantial loopholes and does not include a public registry, experts agree that the movement towards BOT by major economies like the US and UK will be felt around the world.

Among other economies, Ecuador is held up as a model for the amount of publicly available beneficial ownership information. Cyprus, an infamous tax haven, is in the process of establishing a registry, although it is not the public registry required of EU member states. Ghana and Kenya, two of Africa’s largest economies, launched their registries in the last quarter of 2020.

Many other countries have begun the process of establishing and enforcing BOT registries, based on their membership in international groups. The EU, for example, required members to have public registries by the end of 2020. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) also requires member states to register beneficial owners in the extractive sectors.

The state of BOT regulation currently is fluid and growing quickly. But even with this progress, criminal and corrupt actors will not want to start playing by these new rules. They will keep finding new locales to exploit, until all jurisdictions recognize the importance and take steps toward full BOT. In the meantime, several organizations study and advise on best practices for establishing BOT regulation and track such legislation globally. See Box 2.

Box 2: Key international instruments and initiatives establishing BOT guidance and recommendations

- G20 and its High Level Principles on Beneficial Ownership Transparency

- Financial Action Task Force (FATF): global watchdog on money laundering and threat finance. Sets standards for harmonized regulation on these issues. Issued their first wildlife crime guidance in 2020.

- Financial Accountability and Corporate Transparency (FACT) Coalition: mostly US-based, advocating for fair tax policy that address corrupt financial practices.

- Tax Justice Network: works to reform financial and tax systems from perspective of inequality, corruption, and democracy. Maintains the Financial Secrecy Index.

- Transparency International: advocates for full transparency in all public sectors including noting the importance of BOT to address corruption and environmental crime.

- Open Ownership: technical and policy experts provide support and guidance to companies, governments, and civil society on all aspects of BOT reforms.

What can practitioners do?

There are many ways NRM and conservation practitioners can consider BOT to enhance decision making, safeguard projects from corruption and illicit financial flows, and leverage BOT for their work.

- Know the benefits of BOT for key conservation goals, across natural resource sectors

- Fisheries managers and practitioners can implement or advocate for BOT requirements to help identify, hold accountable, and deter owners of fleets and vessels that overfish or commit human rights violations.

- Forest practitioners can use BOT to strengthen their efforts to influence government and industry to uphold environmental commitments. For example, WWF announced in 2021 it was ending its long-running relationship with paper company Domtar due to Domtar’s acquisition by Paper Excellence. Paper Excellence is affiliated with Asia Pulp and Paper (APP), which has a record of hidden ownership of companies engaged in unsustainable forestry practices and social conflict. Journalistic investigations have been required to unravel the extensive beneficial ownership networks involved with APP.

- Beneficial ownership data can be used to analyze wildlife trafficking networks and the web of businesses through which money and goods move. For example, the UK Border Force was able to arrest a glass eel trafficker in 2017 by cross-referencing evidence from a front company with the country’s beneficial ownership registry, ultimately identifying the individual involved.

- Understand the law where organizations work and consider enforcing corporate norms to ensure beneficial ownership can be established before hiring, paying, or otherwise working with a company. NRM practitioners stewarding public funds should take note of BOT requirements of both the funding country and the country in which they are working. With ongoing change around BOT, such planning and institutionalized practice will ensure compliance and protection of programs. Questions to ask during due diligence include:

- What types of business must comply? Corporations? Trusts? Partnerships?

- Does BOT apply only to newly formed companies, or existing ones too?

- How is beneficial ownership defined, and what info is collected?

- Is the registry public and searchable? If not, do groups have access that could be potential allies (e.g., banks or investigative agencies).

- Note the signs that an entity may have obscured ownership.

- Is the company registered in a low enforcement jurisdiction without transparency requirements? The Tax Justice Network tracks the risk levels of countries based on their regulatory requirements as part of its bi-annual Financial Secrecy Index.

- Does the ownership information registered make sense? What other companies do they own? Are they transparent about who makes decisions? Do their stated work practices or tenure in business make sense for the work they want to do for the project or organization?

- Verify the beneficial owner(s) of the living and working spaces the organization leases. Real estate is a common asset for corrupt actors to purchase, often with only the legal owner rather than the beneficial owner recorded. Practitioners should take care that they do not inadvertently contribute funds to corrupt schemes, criminals, or money laundering operations.

- Recognize that anonymous companies are created and exist all over the world. Beneficial ownership secrecy is not only a problem in locations historically viewed as tax or secrecy havens. Assumptions that one’s work is in a low-risk location are dangerous, particularly given the risks of corruption and exploitation in NRM.

Learn more

- “Money Laundering and the Illegal Wildlife Trade.” Financial Action Task Force, 2020. https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/Money-laundering-and-illegal-wildlife-trade.pdf

- “Case Digest: Initial Analysis of the Financial Flows and Payment Mechanisms behind Wildlife and Forest Crime.” TRAFFIC, 2020. https://www.traffic.org/publications/reports/case-digest-an-initial-analysis-of-the-financial-flows-and-payment-mechanisms-behind-wildlife-and-forest-crime/

- “A Beneficial Ownership Implementation Toolkit.” OECD and Inter-American Development Bank, March 2019. https://www.oecd.org/tax/transparency/beneficial-ownership-toolkit.pdf

- “Making central beneficial ownership registers public.” Open Ownership, May 2021. https://www.openownership.org/uploads/OO%20Public%20Access%20Briefing.pdf

[1] For the purposes of this introduction, we will use the word “company” or “entity” to describe the collective of companies, trusts, fronts, shells, etc.

[2] Thomas directly owns 25 percent of Timber Company (TC), therefore he is a beneficial owner. Maria directly owns 15 percent and, indirectly, (0.8*0.3*0.51)*100 = 13.24 percent. Combined, Maria owns therefore owns 28.24 percent of TC, making her a BO. Robert indirectly owns (0.19*0.51)*100 = 9.69 percent of TC, therefore he is not a BO. Leonard indirectly owns (0.2*0.3*0.51)*100 = 3.06 percent of TC, and is therefore not a BO. Diana indirectly owns (0.51*0.51*0.51)*100 = 13.27 percent of TC, and is therefore not a BO. Adapted from: https://www.twobirds.com/en/news/articles/2017/denmark/registrering-af-reelle-ejere

[3] According to reviewers, regulators do not currently have the statutory power to do so, but soon will.